The Hoosier National Forest covers an unlikely but extraordinary piece of history just outside of Paoli — a large pioneer community of free Black settlers called Lick Creek. The settlement flourished from about 1833 until the end of the Civil War, and included the son of a Revolutionary War soldier who had been at Valley Forge. The brother of the first African American U.S. senator helped organize the two churches that would thrive in Lick Creek. One man in the first generation of people born in the settlement participated in the siege of Fort Wagner in South Carolina, the Civil War attack portrayed in the movie Glory.

Lick Creek is a story of a burgeoning community of free Blacks, of economic and legal independence, but also of racial animosity, fugitive slave catchers, racist laws, conspiracy, and treason.

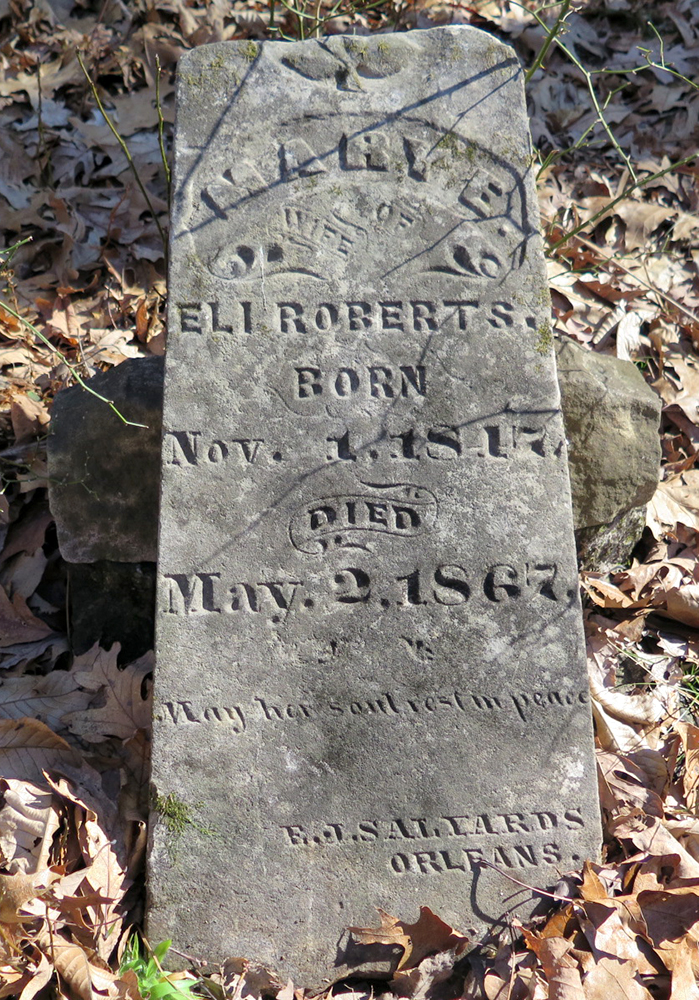

The Lick Creek settlement began in 1831 with 80 acres of U.S. government patent land purchased by 22-year-old Mathew Thomas. A cemetery still stands on the site, including a grave marker for Mathew Thomas’s wife, Mary. | Limestone Post

Ryan Campbell, associate director of the Center for Archaeological Investigations at Southern Illinois University–Carbondale, has excavated sites in this pioneer community, including a farmhouse owned by Solomon Newby. “It’s pretty special to think about [this community] during that period of time, because it’s right at the beginning of African Americans trying to set up lives outside of slavery in some of these new states and territories,” he says. “It’s really a unique place, because you get to see that develop through time.”

Quaker allies and free Black families moved to the area before Indiana was a state, and by 1820, census data show 11 Black pioneer families living throughout Orange County. While the first African American landowners homesteaded in 1817, the Lick Creek settlement, near what is now Chambersburg, began in 1831 with land purchased by 22-year-old Mathew Thomas, who bought 80 acres of U.S. government patent land.

At the time of the first Black settlements, Indiana had none of the racially oppressive laws that had burdened people of color in North Carolina. Yet on October 29, 1833, about a year and a half after his land purchase, Mathew Thomas had witnesses write “free papers” for him, an affidavit witnessed by Quaker men in the area. “These statements are made with a view to save the said Mathew from malestation [sic] of those who might probabley [sic] apprehend him as a slave.” Because Mathew was free-born, the affidavit continued, he had a “right to the exercise and enjoyment of all the rights and privileges guaranteed by the constitution and laws of the country to free persons of color.”

Mathew probably carried his free papers with him, but in August 1853 he also recorded them in the then newly built Orange County Courthouse in Paoli, where they remain today. Mathew’s commission of his free papers in 1833 and their recording in 1853 coincide roughly with the passage of Indiana’s most racist laws, enacted to restrict Black immigration and settlement and to deny Black people the ability to get ahead economically.

Indiana Governor James B. Ray said this to the General Assembly in 1829, insisting that the laws of slave states near Indiana meant white Hoosiers were under siege from freed slaves:

“(I)t is your right, to regulate for the future, by prompt correctives, the emigration into the State and the continuance of known paupers thrown upon us from any quarter. … If they cannot afford, by sureties, indemnity to our citizens by reasonable time, should be thrown back into the State or country from whence they came.”

A letter to an Indianapolis newspaper at the time was more hateful, referring to people of color as “dregs of the offscourings of slave states.” Much like today, there was at least a two-pronged argument against immigration, that taxpayers would be forced to support Black newcomers and that slave states were not sending their best people to Indiana.

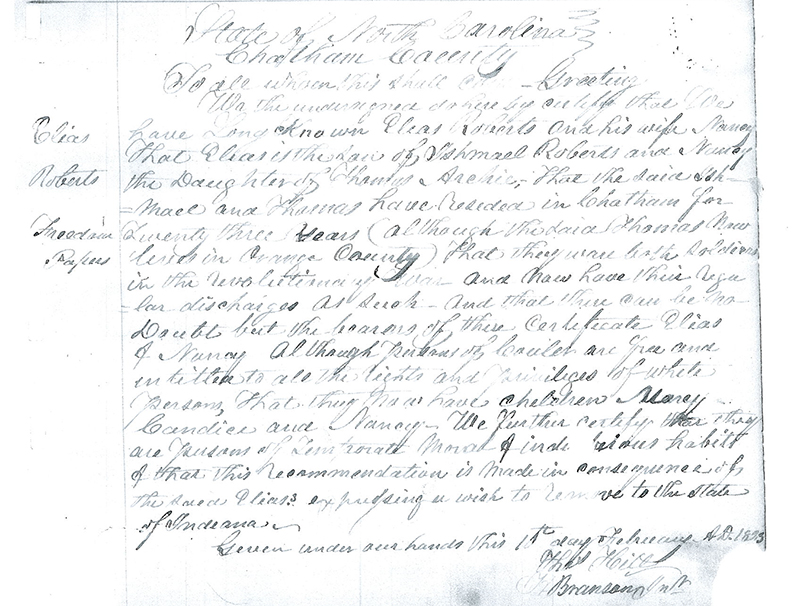

Lick Creek settler Elias Roberts’s freedom papers, also called “free papers.” Roberts once owned 640 acres in three different spots at Lick Creek to help other Blacks settle in the area. See the end of the story for transcriptions of the freedom papers for Elias Roberts and John B. Thompson. | Courtesy image

Governor Ray got his wish when in 1831 the law decreed that any free person of color post a bond of $500, more than $14,000 today, or face expulsion from the state. In 1851, Indiana enacted a second constitution, which forbade African Americans from coming into the state at all. The legislature also passed laws that required Black people already living in the state to register with the county clerk, a record which came to be known as the Negro Register. The law rendered all contracts with Black people — including land sales — void. It also fined African Americans who violated the law and white people who employed African Americans $500. Any fines collected through this scheme were supposed to pay for African Americans to go to Liberia, but few Hoosiers of color emigrated to the African colony. The laws were mostly unenforced, but they expressed the increasing racism among white Hoosiers in the buildup to the Civil War.

Yet African American farmers at Lick Creek continued to thrive until the Civil War, not just economically but as a culture. In the 1850s, Black land ownership in Lick Creek peaked at about 2,300 acres. For purposes of comparison, the Indiana University–Bloomington campus is 1,939 acres.

Angie Doyle, heritage program manager for Hoosier National Forest, began working for HNF in 1992 and has developed research and partnerships to learn more about Lick Creek as time and funding allow. Lick Creek was integrated with white settlers living next to Black-owned farms. “So far as I can tell, there was no discord among neighbors,” she says. Relative peace among neighbors and economic interdependence may have been part of the reason the community did well despite increasing hostility reflected in the law.

Archaeological work done in partnership with the Hoosier National Forest and Southern Illinois University–Carbondale, for example, uncovered broken ceramics and glassware. Campbell wrote in his professional report of the excavations that “These vessels were as nice as any from farmsteads inhabited by their EuroAmerican neighbors.” These signs of everyday comfort, as well as the property values cited by the Black pioneers in the census data, suggest that African American settlers were doing as well economically as many of their white counterparts. It’s also evident from his report that a lot of pigs met their end at the homestead his team excavated, suggesting that the Black settlers had not only whatever they could grow and gather, but ham and bacon, too.

Archaeological work done on the Lick Creek site suggests that the Black settlers were doing as well economically as their white neighbors. | Photo courtesy of USDA Forest Service

There is also evidence that Black pioneers were ambitious in growing their community. Since part of Doyle’s job is to inventory and document historic sites located on public land, her archival research points out that a Black pioneer named Elias Roberts bought land purposely to encourage people of color outside the community to settle there. At one point, Doyle says, Elias owned 640 acres in three different spots at Lick Creek, although she is not sure whether his intent was to rent, sharecrop, or sell this farmland to newcomers.

Elias’s free papers, made in 1823 in North Carolina, tell us that he and his wife, Nancy, were children of Revolutionary War soldiers Ishmael Roberts and Thomas Archie, respectively. Ancestry.com records reveal that Elias’s father served for 84 months, including in the Battle of Brandywine Creek and at Valley Forge, while Nancy’s father likely enlisted as a teenager near the end of the war. Elias and Nancy, who would have eight children, prospered at Lick Creek. When Elias died in 1866, he left behind a large farm, five plows, three horses, four head of cattle, sheep, pigs, and stores of tobacco and grain.

The Lick Creek settlement began in 1831 with 80 acres of U.S. government patent land purchased by 22-year-old Mathew Thomas. Hoosier National Forest’s Lick Creek Trail, pictured here, passes through the area. | Limestone Post

The Lick Creek Trail of the Hoosier National Forest goes past the Roberts and Thomas homesteads, now covered with trees, and it is apparent the living wasn’t easy. “It’s a pretty rugged environment — those hills are not easy to traverse — and my guess would be that the land that the African Americans got was probably not the prize land,” says Campbell. “I imagine the areas along the more regular streams and rivers in that area were preferentially getting taken up by the EuroAmerican settlers that were moving into the area.”

Campbell believes that the Lick Creek pioneers intentionally created a culture that was different, more progressive, than their white neighbors. A lot of white settlers weren’t literate — perhaps because it was not a priority among the skills needed to clear and farm the land. By contrast, getting their children an education was meaningful for Black settlers.

Census data from 1850 and 1860 show that several of the African American pioneers could read, and in 1860 most families had children in school, no mean trick since Black children could not attend local public schools.

For instance, one Lick Creek resident, Harmon Lynch, could not read, but his wife and the rest of his household could, with nine-year-old Matthew and four-year-old Tabitha having attended school at least some of the time.

“It’s maybe a marker of freedom to a degree,” Campbell says. “It’s an important part of developing their identity as free persons to be able to read and write and become educated to set themselves apart from that life of bondage that they or their ancestors might have had, just a generation earlier.”

Campbell also finds evidence of progressive ideals in the location of the settlement. The southern-most part of Orange County was only 20 or 30 miles away from Kentucky, a slave state, and therefore not the safest place for African Americans to live. Although the land in Lick Creek might have been more accessible since it’s along the Buffalo Trace, a historic bison trail used as a road, Campbell suggests the Lick Creek pioneers and their Quaker neighbors might have had another motive for choosing Orange County.

“We think it probably had something to do with the Underground Railroad, and these communities being involved in helping runaway slaves gain their freedom in the North,” says Campbell. “You get the Quakers that are living in the area — the Lindley family who came there originally — we know they were involved in abolitionist activities, so there’s probably something going on with that.” Campbell also notes that there was an African Methodist Episcopal church that thrived in Lick Creek beginning in the 1840s. Nationally, the AME church was involved in abolition, so it makes sense that Lick Creek would have been involved in abolitionist activity or sheltering other Black people seeking freedom.

Campbell says there are no direct records indicating this, not least because the Underground Railroad activity was against the law. Nicole Etcheson, an Alexander M. Bracken Professor of History at Ball State University, has researched Black families who lived in Putnam County during and after the Civil War, and she agrees such things are hard to verify.

In the 1850s, Black land ownership in Lick Creek peaked at about 2,300 acres. Tombstones of settlement families, such as this one from the Roberts family, remain in Hoosier National Forest. | Limestone Post

“I’m afraid that a lot of African American history involves informed speculation,” Etcheson says. “It’s frustrating, but you often can’t pin down exactly what happened.” This is especially true of rural settlements where there were fewer people and organizations who kept membership records, she says.

Most Lick Creek pioneers likely were members of its two African American churches, the Union Meeting House and the AME church built next door. The AME church in Orange County attracted a larger membership and was originally presided over by Rev. Willis Revels, who was also the older brother of Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African American senator from Mississippi.

But even here there are organizational records missing. Although the AME churches were well organized and connected, with membership reported at annual conferences in Chicago, there is a gap in these files between 1845 and 1867. Coy Robbins, a Bloomington man who collected many of the original documents about these Black pioneers in his 1994 book about Lick Creek, Forgotten Hoosiers, wrote: “The Indiana AME Church leaders may have decided to discontinue releasing information about the location of their small, isolated, primarily rural congregations in order to protect their members from racial harassment or being kidnapped as runaway slaves.” If the AME Church in Lick Creek was also pursuing abolitionist activities, this is another reason for scant records.

One can’t help wondering about the people who built this settlement though, and although the Negro Register feels like a Hoosier version of the Nuremberg Laws in Nazi Germany, the written descriptions are fascinating. Robbins recorded all of the registers he could find in the state in 1994, including Orange County’s, which contain 141 entries between 1853 and 1861.

In the year he registered, for example, Harmon Lynch, who ensured everyone in his house was educated, was 6’2”, “heavy beard, scar on top of left arm.” Elias and Nancy Roberts, the children of Revolutionary War soldiers, were both described as “gray hair, heavy set,” at 64 and 54, respectively. Mathew Thomas, the founder of the settlement, was 45 when he registered in 1853, only 5’3”, and “quite dark.”

The archival and physical evidence of Lick Creek seems to go back and forth. On one hand, the community was integrated, peaceable, prosperous enough at a place where most people, Black and white, were often subsistence farmers. There is evidence of community and education, ideas and ambition.

On the other hand, there are harsh reminders of danger and hatred that bore down on these folks — in racist laws, registers, and rhetoric, the implications of missing church records, or an article such as appeared in the Paoli newspaper, The American Eagle, on July 2, 1857. The article tells of three Black men hunted by a fugitive slave catcher, one who was captured, one who was shot dead by his pursuer, and one who was protected when an elderly white man and his son appeared with a drawn gun. Likewise, a woman who’d lived as a free person in Washington County, which adjoins Orange County, was seized by a slave catcher a few years earlier and never heard from again.

While many families suddenly left Lick Creek in 1862, others spent the rest of their lives there. | Limestone Post

Black pioneers were clearly under more pressure as the Civil War approached, so it’s not surprising that they began to leave Lick Creek during the 1860s. While nobody knows the exact population of Lick Creek, African American population in Orange County peaked at 260 in 1860, according to Robbins, and declined by 101 residents, almost 40 percent, by 1870. According to the same source, Mathew Thomas’s son William, the last surviving resident of Lick Creek, sold his property in 1902.

Most startling, in September 1862, seven Lick Creek families — headed by Harmon Lynch, Isaac Scott, Alvin Scott, Joseph Scott, Solomon Newby, Jarmon Rickman, and John B. Thomas — sold their farms, totaling 559 acres, and left the settlement. Robbins writes that Solomon Newby sold his land in 1862 for about half what he paid for it in 1846, losing not just half his purchase price but all the improvements the family had made in 16 years. He writes that Newby must have left under “extreme duress.”

Campbell believes that the institution of the Civil War draft in October 1862 might have been a factor. “I think it’s just too coincidental that it coincides with the forced conscription with soldiers a month later, so able-bodied men from Orange County would have been forced into the draft,” he says. “My guess would be that those families, for whatever reason, either didn’t want to take part in the war, or felt like they were being forced into something that they did not want to take part in, or the North wasn’t going to win, and they’re ready to just move on and get out of the United States entirely.”

At least six of these seven families moved to Kent County, Ontario, Canada, near Detroit, according to Ancestry.com records, and the seventh, Joseph Scott and his family, might have moved out of the reach of census data or has too common a name to pin down. Because those families wound up in Canada, Campbell says, they got “an entirely different government to live under, so I think that has to have something to do with the fact that those families left when they did.”

Campbell and Etcheson also agree that these families might have been subject to racial harassment by local vigilantes or Copperheads, Southern sympathizers who were often pro-slavery and were against Indiana’s participation in the Civil War.

Lick Creek family members buried in the cemetery are still remembered today. | Limestone Post

Robbins writes in a short footnote in his book that “Secret societies, such as the Knights of the Golden Circle and the Sons of Liberty, operated in Orange County between 1861-1865. One of their expressed goals was to drive all people of color from Indiana.” Robbins cites as his source History of Lawrence, Orange, and Washington Counties, Indiana, published in 1884 and written by brothers Charles, Weston, and LeRoy Goodspeed.

Robbins’s footnote is an understatement. The Goodspeed history is remarkably straightforward about how racist and treasonous the Knights of the Golden Circle and the Sons of Liberty were. But then again, William A. Bowles, a major general in the Knights of the Golden Circle and prominent Orange County resident, was one of four men convicted of plotting to overthrow the federal government in the Indianapolis treason trials of 1864.

Bowles was a two-term state legislator and built the first French Lick Hotel. According to the Goodspeed history, Bowles was also charged in 1820 with digging up a dead body. He owned a liquor store in Paoli in 1828 and erratically published a newspaper, which he abandoned after a year and a half. He was indicted for practicing medicine without a license, but had the indictment quashed.

In 1858, Bowles was convicted of bringing seven slaves from out of state. Bowles said they were the property of his Southern-born wife, Eliza, and that they were in ill health and he was bringing them for treatment in the hot springs. Later he gave up that defense and pleaded guilty. Eliza would divorce him in 1868 and win $25,000 (more than $400,000 today) from a sympathetic Orange County jury to compensate her for her husband’s “improper conduct.” Despite all of these details in the Goodspeed history, the Goodspeed brothers describe Bowles as an “able” man, even while giving a brief synopsis of his treason, possibly because he’d been an officer in the Mexican-American War.

At Bowles’s trial for treason in 1864, a witness would describe that Bowles was drilling paramilitary groups in Orange County and plotting the takeover of Camp Morton in Indianapolis. He and his co-conspirators planned to release the Southern POWs held there, arm them, and lead the POWs and his militia to take over the Indiana government and legislature. He and three other conspirators were convicted of treason against the United States and sentenced to hang.

Bowles’s death sentence was commuted by President Andrew Johnson in May 1865 and his conviction overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1866.

The Orange County Courthouse in Paoli was built around the time of the Lick Creek settlement. Mathew Thomas entered his free papers into the courthouse’s records in 1853 and they are still located there. | Limestone Post

Bowles was an avowed white supremacist. In February 1861, a few months after President Abraham Lincoln’s election spurred South Carolina and a handful of other Southern states into seceding from the U.S., Bowles and others convened a meeting in French Lick, passing a resolution that “This was a white man’s government, regretting the severance of the Union, opposing the coercion of the Southern States, and expressing sympathy for the South in the perversion of the Constitution by the President of the United States.”

The Goodspeed history also describes that in Orange County, Unionist men had their crops burnt and were threatened with expulsion from the county. So strong was Copperhead sentiment that Southern deserters were invited to take refuge in the county, while Union Army recruiters were threatened with death. Yet, as the Goodspeed history notes, Orange County easily met its quota for the draft in October 1862.

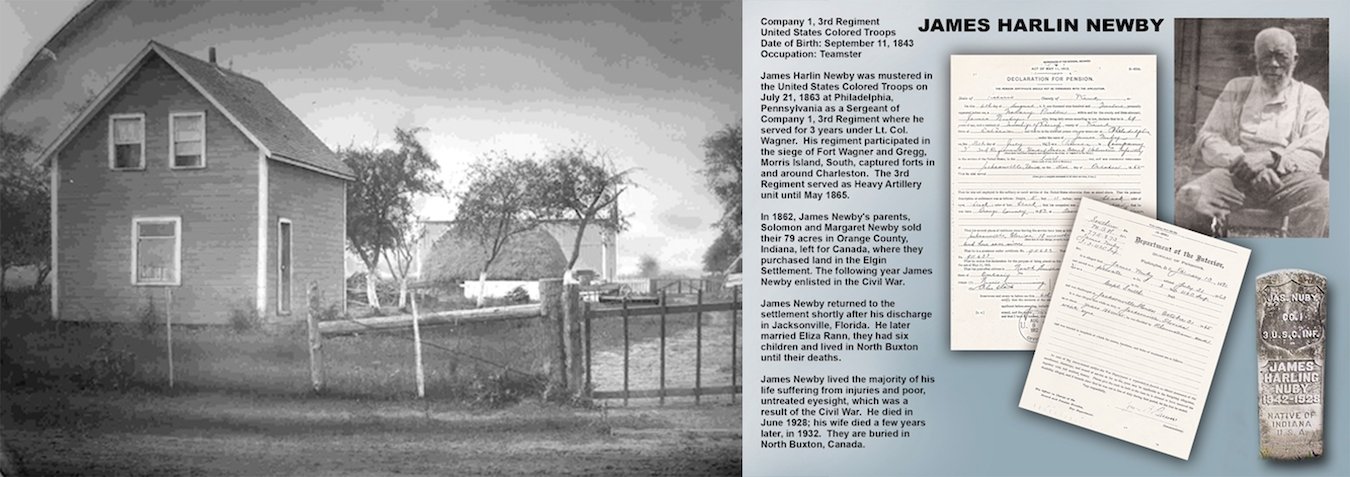

One of the young men who registered for the draft in Orange County was 20-year-old James Newby, the son of Solomon Newby. James remained in Orange County after his family left for Canada, but instead of joining the military in Orange County, he made his way to Philadelphia, where in June 1863 he joined the 3rd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). While the 54th USCT infantry made the famous assault on Fort Wagner, portrayed in the movie Glory, James’s unit participated in its subsequent siege.

It’s hard to imagine, with the level of vitriol and hatred perpetrated by Bowles and his ilk, that there wasn’t some racial harassment and violence in the large Lick Creek settlement not far from Bowles’s residence in French Lick. Despite possible harassment, many settlers, especially those who had been there longest, like Mathew Thomas and Elias and Nancy Roberts, stayed.

Whatever motivated Solomon Newby and his fellow Lick Creek pioneers to move to Canada, it seems as if life might have ended happily for them.

Six families left Lick Creek and moved to Kent County, Ontario, Canada, and joined a settlement there. Pictured here is the Lick Creek Trail. | Limestone Post

The Buxton Museum in Kent County, Ontario, Canada, is built on the farm of Solomon Newby’s son, James, the young Hoosier who had gone to Philadelphia to serve in the USCT. Solomon and the rest of his family had bought land after they moved to Canada, and James later joined his parents and homesteaded there himself after the Civil War. The Buxton Museum curator, Shannon Prince, is one of the descendants of the Black farmers who made their way to Canada to settle in the Elgin settlement, a colony of former fugitive slaves, begun by Rev. William King, a white Presbyterian minister. Prince says that King had inherited slaves, but he knew that slavery was immoral and wanted to bring them to a place where they would have better opportunities.

Prince says King found 9,000 acres of heavily forested land held by the British church along Lake Erie and near the Thames River in Ontario. He knew that these waterways would help refugees travel there, so he and group of shareholders, Black and white, pooled money to buy the land and started the settlement with his 15 former slaves in 1849.

Early Canadians also opposed living near people of color, even though Canada had abolished slavery, according to Prince. “[King] wanted to dispel those myths, so he said, ‘Give Blacks the same opportunities as whites, and they can become self-sufficient.’ So he put a lot of rules in place. You could not share-crop, you could not rent, and if you sold it was only to be to Blacks. Your homes had to be certain size,” Prince says. “He put these rules in place for ten years, to prove to the people in the outlying areas, ‘Look how successful they are,’ but he also wanted to instill that pride in the Blacks themselves. You know a lot of them were coming from being enslaved to being free, and a lot of them couldn’t really grasp that concept. You know: ‘I own myself. My land, my property, myself.’”

Prince says that after abolitionist newspapers started spreading the word of the Elgin settlement, people came. Ironically, there was a November 17, 1834, article in the Paoli American Eagle about the allegedly poor living conditions of Blacks who had fled the U.S. for the Ontario cities of Chatham and Amherstberg. The article was condescending toward the Black refugees, whom it portrayed as being cast adrift among a hostile Canadian population by feckless abolitionists who had “encouraged” their escape without providing financial support or moral instruction. Nevertheless, the article grudgingly admitted that “a few of [the Black settlers] are doing well in different kinds of businesses,” and that these cities were one-third Black. The Eagle article may be how the Lick Creek settlers read about Black communities in Canada.

“You received 50 acres, but you were charged $2.50 an acre, and you had ten years to pay that off,” says Prince. Education was important in Elgin, just as it was in Lick Creek. The local white school closed its doors to the Elgin community, but Rev. King started an integrated school with 14 Black pupils and two white students. Eventually, the Elgin school was so popular that the white district school was forced to close.

Refugee Blacks walked along the railroads or across frozen Lake Erie to get to Elgin. While it isn’t known how the Lick Creek pioneers went to the Elgin settlement, it is known that Solomon Newby took his free papers with him. Oral history collected by the museum from his granddaughter — “Aunt Muriel, who lived to be 100 and was a library herself,” says Prince — tells how Solomon buried his free papers on his new farm. When he became convinced slavery was no longer a threat, he made a wooden box to house the papers. Solomon died in Elgin at the age of 97. Some of his descendants are still in Canada. The museum still has the box he made for the papers.

Solomon Newby made a box to house his freedom papers while in Canada. The Buxton Museum, located on the Canadian settlement property, still has the box. | Courtesy photo

Prince leads living history tours at the Elgin museum, so she often describes Elgin’s past as if she is speaking of current conditions. Her use of the present tense is probably fitting for a society that still struggles with racism, but it also expresses Prince’s hope that the Elgin settlement will continue its mission to erase prejudice.

“There was no hierarchy [in Elgin] — it was a strong sense of community that was instilled in everybody,” says Prince. “It is really changing the lens of how people are looking at these Blacks, these slaves. The myths are being dispelled, friendships are increasing, because now they’re realizing: They’re just normal people. Different skin color, but that’s it.”

Elgin may have been the ideal for which the Lick Creek pioneers were striving, an ideal they might have achieved had it not been for noxious prejudices and the Civil War. Uncovering and sharing the truth of this African American settlement is a work in progress for people like Doyle and Campbell. Still, as their discoveries unfold, the achievements of these forgotten Black pioneers in Lick Creek are revealed as formidable, inspiring, even exhilarating, against the obstacles they faced.

“We kind of overlay our current cultural understanding on what was going on in the 19th century, which is not the way to do it,” says Campbell. “What [Lick Creek] meant to them, it’s difficult to know. But I’m sure that it felt pretty amazing to move from the South and East, where there were only a few free African Americans, into a community where freedom was the norm. It would have made a huge difference to them.”

Elias Roberts Freedom Papers

To all whom this shall come — Greeting

John B. Thompson Free Papers

Be it known that the bearer hereof John B. Thompson of a light black color rather thick built five feet and a half inches high weighing one hundred and forty eight or fifty pounds and is now in the thirty fifth year of his age is a free born man of color the son of free parents viz Samuel and Elizabeth Thompson and he is a resident of this County is of fair character sober and industrious habits he wishing to travel to the state of Indiana together with his wife Mary who is also free born very fleshy and is the daughter of free parents viz John and Elizabeth Archy. Together with their seven children namely Elizabeth Martha Mary Thomas Sally John & an infant not named and wishing to be safe from molestation witness of the acting Justice of the Peace in and for the said County certify to the above statements and confidently recommend the said John B. Thompson and family to the care protection and Employment of those amongst Whom his lot may be cast given forth from under our hands and seals this the twenty first day of the 8th month August 1845.

James H. Newby and his wife, Eliza Rann Newby, at their home in Canada. James was born in Orange County, Indiana, and registered for the Civil War draft when he was 20. After his parents left for Canada, James traveled to Philadelphia where he joined the 3rd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). After the war, he rejoined his family in Canada, married Eliza, and worked as a farmer. They had six children. | Courtesy photo

(left) The farm in Canada where James Newby worked until his death in 1928. His property is now the site of the Buxton Museum. (right) This exhibit in the Buxton Museum includes a photo of James Newby’s tombstone, which identifies him as a “Native of Indiana, U.S.A.” | Courtesy photos

For further reading, see African American Pioneers of Orange County, Indiana by Donna Pulliam Griffin (available at the Monroe County Public Library), and The Path Along the Creek by Cathy Coulter Qualkinbush.

Correction: The caption of the feature photo at the top of the story originally identified the body of water as Lick Creek. We regret the error.